Educators respect and value the history of First Nations, Inuit and Metis in Canada and the impact of the past on present and the future. Educators contribute towards truth, reconciliation and healing. Educators foster a deeper understanding of ways of knowing and being, histories, and cultures of First Nations, Inuit and Metis.

During my 490 practicum in a grade 5 class, I did a unit on plate tectonics and earthquakes. The earthquake portion of this unit was particularly relevant to my practicum class because, living on Vancouver Island, every student had felt at least one earthquake before, and most were excited to recite more exciting earthquake stories they’d heard from relatives or friends.

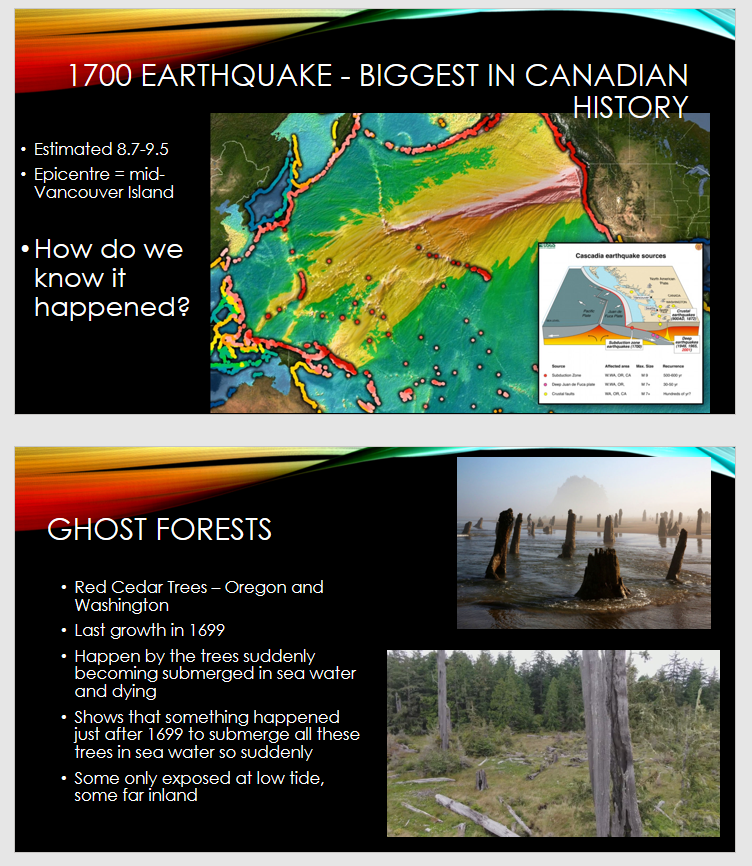

Since earthquakes are something so common on Vancouver Island and have been since the Cascadian Fault came to be, I knew I had to bring in the history of local earthquakes. I started with the largest ones in recorded history, focusing on local implications and pictures from spots nearby that they would recognize.

From there, I went into what is suspected to be the largest earthquake in Canadian history ever: the 1700 Cascadia earthquake.

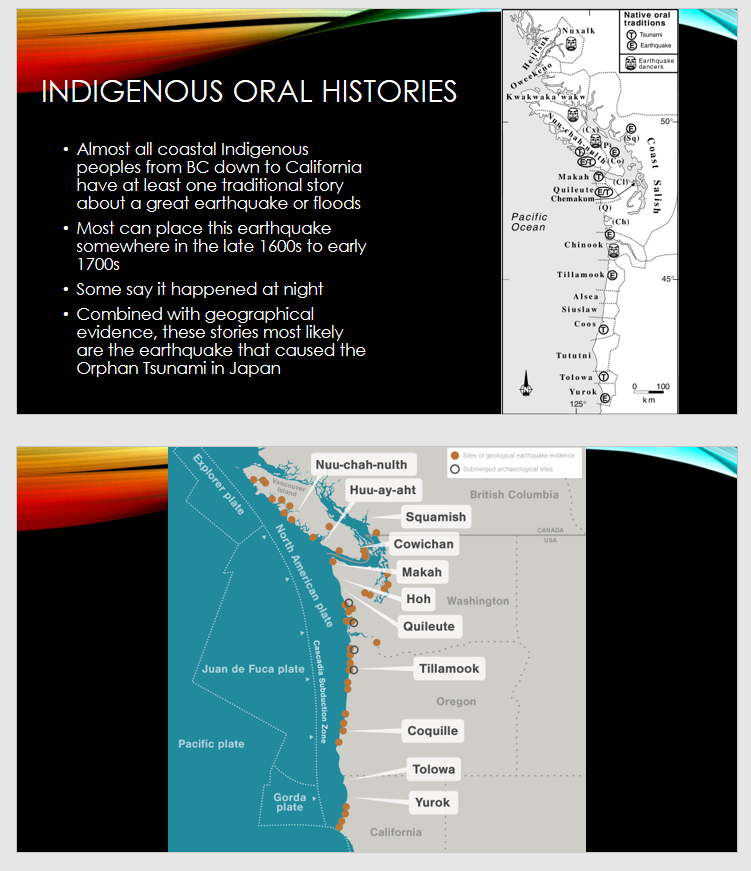

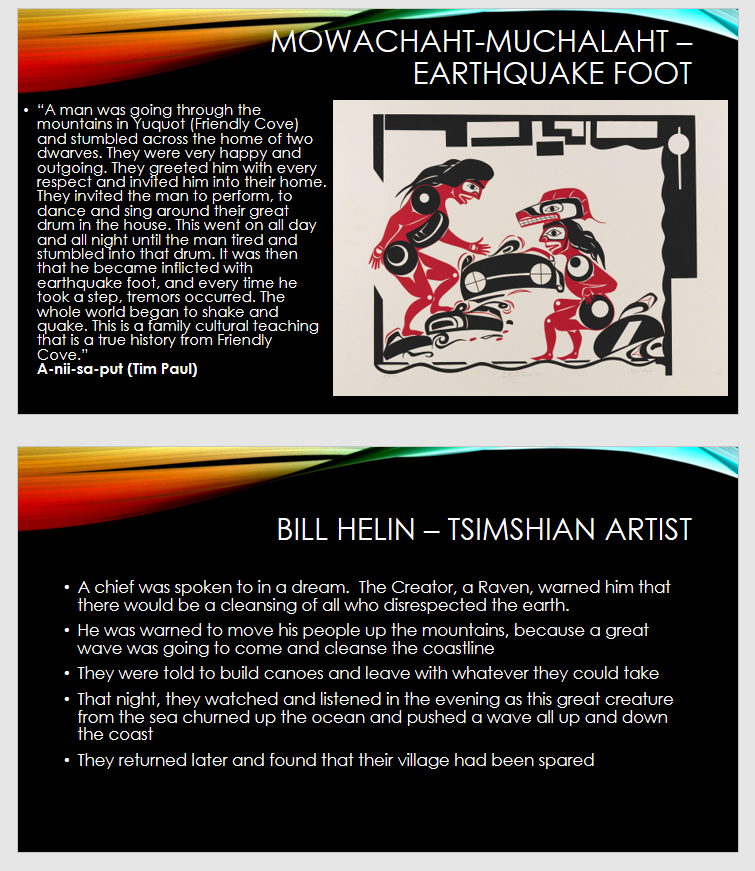

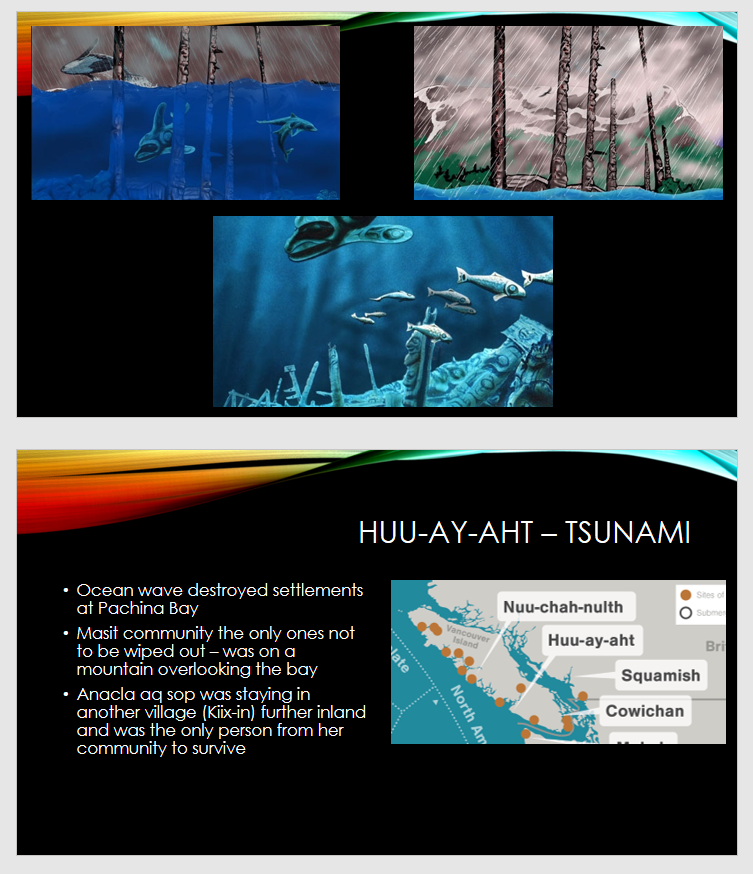

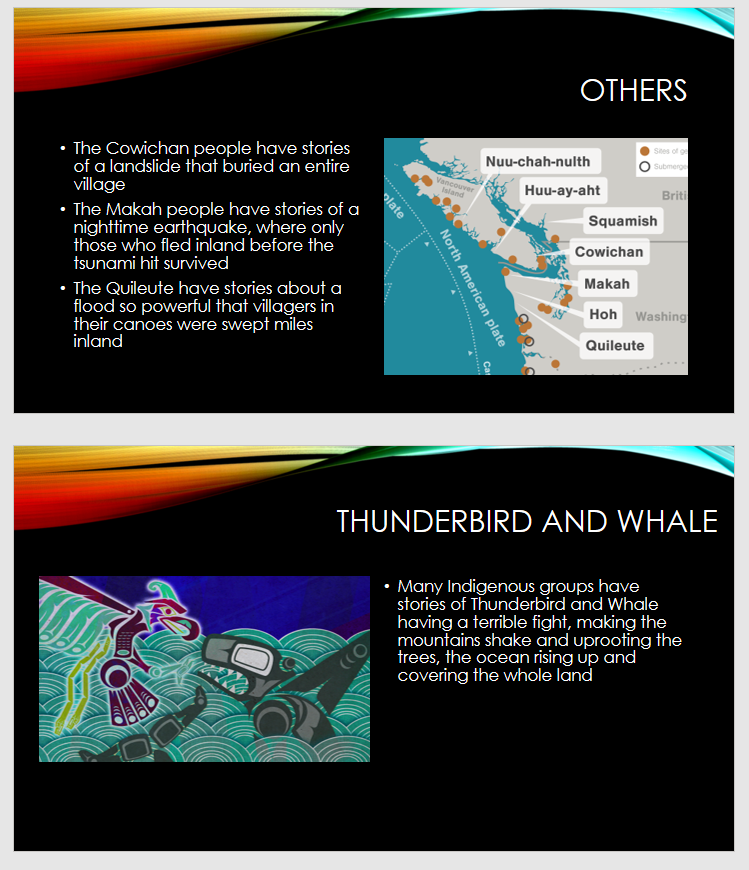

As this earthquake occurred so far in the past, we don’t have records of it in the same way we do today. In my research for planning this lesson, though, I found out that there is a rich oral history of this earthquake, passed down through generations in almost all the Indigenous groups along the Cascadian fault. I researched these stories, found videos online with people telling them, and I brought them into my lesson. While the stories differ between nations, the bones are the same: in the winter of 1700, the earth shook, buildings and trees fell, and, in more coastal communities, huge waves came and wiped out everything in their path.

Doing this research was really enlightening into how much we can learn about the history of the land we live on if we listen to the stories of the people who had ancestors here during that time. From these stories, passed down orally for three hundred years, we know the exact date and even the approximate time that this earthquake happened. Before Indigenous peoples’ stories were given merit, all that was known about the 1700 Cascadia earthquake was that it probably happened, which was only known because scientists valued Japanese written history more and knew from that that Japan had suffered from tsunamis in the aftershocks. Since the tsunamis had to have come from somewhere, it was assumed that an earthquake must have happened somewhere to the east of Japan, where the waves had come from.

But there are so many stories from Indigenous peoples, so much evidence passed down through generations, that we know the specifics of an earthquake that happened over three hundred years ago.

Doing this research for this lesson was really enlightening and intriguing, and I found myself wanting to do more and more, to dive deeper into reading and learning these stories, this history, and had to reign myself in. I only had an hour to do this lesson, my practicum wasn’t long enough to expand it over a few days.

This lesson, though, inspired a rich discussion with my students. The stories intrigued them, and they were able to make connections between what was told in the stories and their own experiences with earthquakes. It was a great lesson, and I will definitely be keeping my notes and PowerPoint for future classes.

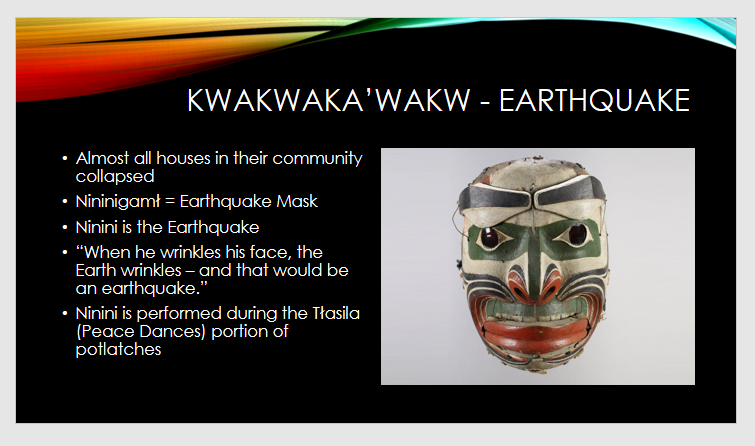

In the future, I think I’d expand this lesson. I might have students look deeper into specific stories, further explore the similarities and differences. A museum near where I did my practicum has Kwakwaka’wakw artifacts on display, particularly a copy of their Nininigami, or Earthquake Mask, which is worn in traditional earthquake dances. It would have been cool to bring my students to the museum, which also houses many other artifacts and stories from the local Indigenous communities. For them to be able to see Nininigami in person, to be able to visualize the history we’ve discussed in class, would have been an amazing experience. Unfortunately, due to the museum being closed because of covid, this was not possible, but is an experience I would like to bring into future iterations of this lesson.